In the last days of October, when the final rays of warmth fall under the chill of autumn, a ghostly feeling of loss hangs in the air. The feeling of cooler weather and the oncoming difficult winter led the Celts to believe it was a time of connection with those in the afterlife over 2,000 years ago. They lit bonfires and left offerings to the souls believed to be wandering the streets. These traditions became known as the festival of Samhain.

From modern-day Ireland, England and the UK, the Celts celebrated the festival of Samhain to welcome back the dead. The Celts were oblivious that this tradition would continue for thousands of years as a holiday known as Halloween. According to history.com, Samhain was celebrated on Oct. 31, which was believed to be a day when the line between the living and dead was blurred and the dead returned as ghosts.

Oct. 31 was also the end of the Celtic calendar and the start of winter, a time heavily associated with death. The Celts had bonfires on the street where animals and crops were burned as sacrifices to the Celtic gods. When performing these rituals, it was believed that Druids and Celtic priests, were more spiritually connected to the dead, which allowed them to predict the future better.

In A.D. 43, the Celts fell to the Roman Empire, resulting in the loss of some traditions. Luckily, a few traditions survived and blended in with Roman holidays that were celebrated around the same time. For the 400 years that the Romans ruled, their festivals of Feralia and Pomona were merged with Samhain, as they were all celebrated at the end of the harvest season. Feralia originated as a day to honor the passing of the dead, while Pomona was the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. As the Romans had many festivals to honor each god and goddess, the day Pomona was honored took place at the end of October. The symbol that

represents her is the apple, which is widely believed to be the start of the tradition of bobbing for apples.

When the Roman Empire was created, it was a pagan nation. However, in the 313 C.E., the Roman Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, resulting in a shift to Catholicism.

In the 7th century, the Catholic Romans established Nov. 1 as All Saints Day, a day spent to honor the saints at the end of the harvest. The holiday was followed by All Souls Day on Nov. 2 to honor one’s dead ancestors. It is widely believed that these holidays were created to erase the pagan festival of Samhain and replace it with Catholic holidays.

In England and Ireland, it was common practice for less fortunate families to go door to door begging for food on All Souls’ Day. The rich families would give the beggars “soul cakes” in exchange for the promise of praying for ancestors who had passed away. This was believed to be the start of the tradition of “trick-or-treating.”

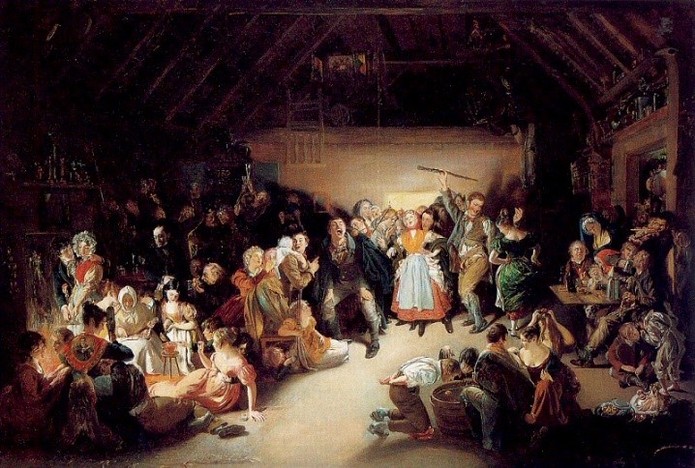

Across the ocean in America, the celebration of Halloween was heavily restricted, especially in the New England colonies until the early 19th century. This was due to the religious background of the event that the Protestants living in America did not approve of. However, the Southern colonies were much less strict and had some festivals similar to those in Europe. The European immigrants brought the idea of Halloween over, and with a large mix of immigrants and Native Americans, play parties emerged in the 1830s. At these festivals, communities would come together to celebrate the end

of the harvest, tell stories of the dead and sing and dance.

While play parties were popular across the country, there was no formal celebration of what is known today as Halloween until the late 19th century, when almost 4.5 million Irish immigrants came to America to escape the Potato Famine. The Irish immigrants carried the traditions that had been associated with the end of the harvest season for centuries over to the States.

Many of the American traditions associated with Halloween came from Ireland such as carving jack-o’-lanterns. jack-o’-lanterns originated in Ireland in the 1800s from a myth about a man named “Stingy Jack” who tricked the devil. He was forced to walk around at night with only burning coal in a turnip to light the way. To scare away “Stingy Jack” and other evil spirits, people would carve scary faces into potatoes or turnips and place them on their windowsills.

In Ireland, it was common for teenagers to pull pranks on Halloween night, a practice that traveled to the States. By the 20th century, putting farmers’ equipment or livestock on roofs, uprooting vegetables and tipping over outhouses were common occurrences on Halloween night.

In the recent century, Halloween has rapidly become a commercialized holiday in the United States. The celebration of Halloween crossed the Atlantic with immigrants, however, many of the activities recognized today were not part of the traditional festivities. Trick-or-treating as it is today rose in popularity in the 1950s. At this point, people would give out fruit, nuts, coins and

toys rather than candy. Passing out candy on Beggars Night sprung about in the 1970s. According to the Library of Congress, companies saw trick-or-treating as an opportunity to sell more. They began to release individually wrapped candies to be given out. Halloween as it is today has still undergone many changes since the late 20th century.

Senior forum monitor Brittany Burkey recounted her high school Halloween.

“Halloween was all about pranks and TPing,” she said.

According to Burkey, high schoolers didn’t engage in partying or trick-or-treating on Halloween.

“It was time for pranks. That was all high schoolers did,” Burkey said.

Some teenagers would also dress up. Some costumes Burkey remembered were, “valley girls, greasers, football players were always big, Frankenstein-type [costumes], zombies were sometimes popular.”

Just a couple decades later in the late 2010s, it was already a completely different landscape. Global history teacher Mikayla McVey recounted her high school Halloween experience.

“No one dressed up anymore, unless it was outside of school at a social gathering,” she said.

The festivities are now leaning more towards parties than pranks.

“Some of the funnest memories are running around late at night, we would still go to the Civic’s association’s haunted house,” McVey said.

For the younger kids of the time, you could expect school parties and dressing up, “We would always have a Halloween party, [where] there would be word searches, and [each person] would bring a different candy and you would go around and take a candy off of each person’s desk,” McVey said.

According to McVey, dressing up for the younger kids had some stand out costumes, “People would [dress up as] Disney princesses, or cheerleaders or witches,” she said.

While the late 2010s weren’t too long ago, Halloween today has undergone significant changes. Today it’s still unlikely for high schoolers to go trick-or-treating, but there have also been some unexpected changes to trick-or-treating with younger children.

“The biggest change is trunk-or-treat that people do now,” McVey said.

Trunk-or-treat is a relatively new activity for elementary or younger children to participate in that arose from parents wanting something different than house-to-house trick-or-treating. NPR stated that trunk-or-treating was started for parents who wanted a safe alternative to their kids going door-to-door as well as being helpful for those in rural areas.

Trunk-or-treating hasn’t fully taken over yet. This fall in Upper Arlington, people still dressed up in costumes and walked the streets, going door-to-door on Beggars Night. Hundreds of people also attended the Golden Bear Scare in mid-October. Teenagers got together for costume parties and attended haunted houses with friends and family.

What today is viewed as a commercialized holiday, dates back to a pagan festival in the first century. Samhain, a holiday celebrating the belief of souls walking the streets has turned into parents and kids alike dressed up walking the streets in their own ghostly fashion. The growth of Halloween from its roots thousands of years ago was a slow process of the mixing of different cultures, religions and stories. The traditions that sprung up from the centuries of change are not stagnant, they will continue to grow and adapt with the times today, molding into whatever the future holds.