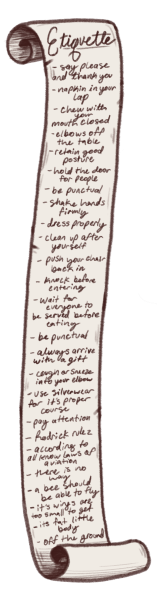

“Keep your elbows off the table,” “say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’” and “hold the door for the person behind you” are all common practices of etiquette that people instinctively abide by daily. Rules like being punctual and waiting until everyone has been served to start eating have been around since the 17th century and more have evolved as time has gone on.

Etiquette is defined by Merriam-Webster as the conduct or procedure required by good breeding or prescribed by authority to be observed in social or official life. However, etiquette means something different to everyone, varying based on age, nationality and time period.

According to Historic UK, etiquette originated in France when King Louis XIV used small placards, called “etiquets,” to remind courtiers of the accepted house rules. These preliminary rules then evolved and were adapted into many countries’ societies. Every culture throughout history has been defined by the concept of etiquette.

But if these directives were implemented into society hundreds of years ago, are they still relevant today?

A HISTORY LESSON

The term “etiquette” was coined in the 1600s and 1700s by King Louis XIV’s gardener in an attempt to keep aristocrats from trampling the grass at Versailles. Thus, etiquette was used to mean “keep off the grass.” Eventually, etiquette expanded to include the rules of where to stand and how to act at court functions. Of course, as language evolves, so does etiquette; etiquette looks significantly different today than it did in 17th century France.

“Of course [etiquette] develops—just as language, law and other tools by which we live keep adjusting to changing conditions,” Judith Martin, a columnist for the Washington Post said. “The underlying principles are permanent, but the forms by which they are expressed not only change over time, but vary in different societies and in subsections of those societies.”

Although etiquette technically only dates back to the 1600s, evidence of social norms and manners exist from much earlier. Ancient civilizations had their own sets of rules for how to behave, which have been recorded in different ways.

For example, Ancient Greece had specific guidelines as to who sat where during meals. The noblemen sat in high armchairs, while the lesser people sat in shorter chairs that didn’t have footrests. Additionally, the men sometimes laid at the table on a couch called Klinai, with their wives sitting on the foot end. The Greek adopted Klinai after the Persian Wars, demonstrating the spread of social rules across cultures.

Similarly, the Ancient Egyptians had their own manners and customs, which can be inferred from written records and art depicting the way people function in society. Ancient Egyptians ate with their hands instead of utensils and used a single bowl for the whole table. Some ancient values may seem unorthodox to some, such as it being considered rude to point any part of your foot towards someone. Other rules are still relevant to today’s society: people are expected to show gratitude when complimented, greetings are customary before joining a conversation and young people are often expected to show respect to their elders.

In the Middle Ages, the standard for manners came from chivalry, a system for knights that guided religious, moral and social code. The Code of Chivalry outlined expectations such as loyalty, bravery and respect, as well as courtesy for battle.

Etiquette especially flourished during the Renaissance, along with art and culture. Table manners as are widely accepted in the Western world today were established during this time period. Common rules in Renaissance Italy include chewing quietly, washing hands before a meal and avoiding scratching and spitting at the dinner table—these rules are still applicable today.

Despite constant developments, Martin notes that no time period is “more polite” than another—they are simply different.

“People who believe that the world used to be more polite forget that such politeness was directed toward a limited segment of society, excluding vast numbers of people,” she said.

Studying the history of manners and social rules sheds light on the development of etiquette across time. Each generation alters what is considered “proper etiquette” to fit a constantly changing society.

“I highly recommend the study of human social behavior —the dictates of which are known as etiquette— over the centuries,” Martin said. “How we should treat one another has always been a major topic of interest to philosophers, theologians, anthropologists, sociologists, poets, dramatists, and everyone else who is alert to human potential.”

ILLUMINATING ETIQUETTE

Upper Arlington is a community full of traditions, many that hold a strong presence of what some consider “old-fashioned” etiquette. An example of this is Dance Club, a six week program offered at Hastings and Jones Middle School. According to the Columbus Dispatch, Dance Club has been around for almost 80 years and attracts hundreds of students every year.

“Dance club is a club at the middle school that allows students to learn how to formally dance with a partner, as well as some group dances,” senior Kasie Pohlman said.

Students dress formally and gather in the Hastings Middle School cafeteria once a week.

Dance Club provided an opportunity for students to learn something new and get a sense of the “proper” way to dance and politely interact with people.

“I thought I got me out of my comfort zone to do things that you weren’t really used to doing, and it kind of helped you grow confidence,” senior Mary Backiewicz said.

Both Pohlman and Backiewicz participated in Dance Club at Hastings Middle School, along with many others who enjoyed the experience.

“I always enjoyed getting dressed up to go and doing the big group dances,” Pohlman said. “Dancing with a partner you’d never met and being told to make small talk was always a little awkward I must admit, but overall it was a good experience.”

Students were to form two lines: one of boys and one of girls. Through these lines, pairs were made between students and each pair was to introduce themselves and share personal facts with each other.

But through these classes, students learn that there’s more to slow dancing than hand placements and foot steps.

“I remember before you asked someone to dance, they had you introduce yourself, which I thought was really good because they kind of want you to get to know who you’re dancing with,” senior and previous Dance Club member Julia Hahn said.

Communication skills, posture, and consent are all life lessons that students recall learning through the club.

And while the central goal of Dance Club was teaching kids how to slow dance, Hahn found that she’s never really used those lessons.

“I would say like sometimes at school dances… they’ve been like okay, now it’s time [to] slow dance or whatever, but I never have done it. I always just, like, step to the side and go to a different place,” she said.

Outside of Dance Club, etiquette can also be found throughout establishments across Columbus. The Etiquette Institute of Ohio, founded and directed by Cathi Fallon, offers etiquette classes and training for all ages.

The firm works with big name clients such as Girl Scouts, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Walgreens, and Ohio State University. As their website reads, “through interactive workshops, private coaching and public speaking appearances, [The Etiquette Institute of Ohio] design training to meet the etiquette needs of corporations, universities, organizations and schools.”

Etiquette has also been projected on a national scale through the Washington Post’s column “Miss Manners”, written by Martin.

On the Miss Manners website, Martin is described as, “the pioneer mother of today’s civility movement.” The focus of Martin’s column was the etiquette of not only the time period but the mannerism of people with work, relationships, death, and many other philosophical and nobel dilemmas.

Martin began her column with the desire to improve how people are treated.

“Like everyone else, I want to be treated with respect and consideration, and to live in a peaceful, pleasant environment,” she said. “Unlike nearly everyone else, I realize that this requires me to treat others with respect and consideration.”

She has succeeded in making etiquette a more widely discussed topic, garnering an audience of millions over the span of her career. Martin’s work is published in over 200 newspapers across the United States. However, her popularity has not had the results she would like.

“I would like to civilize the world, but unfortunately that hasn’t happened yet. At least I have put the topic of civility on the national agenda,” Martin said. “Everyone now talks about it, although generally without taking the next step of practicing it.”

Sororities are another common representation of outdated etiquette, seen with the establishment of house moms and other rules unique to each university.

But for Evelyn Taylor, a junior at Miami University, her sorority looks different than how the stereotypes portray them.

“So since we don’t have sorority houses, we have sorority dorms. So I live on a floor with my sorority in Miami’s dorms,” she said. There are many speculations as to why Miami is structured this way and Taylor explains that one rumor goes back to 1974 when Miami converged with Western College.

“[Western College] was a stern college that used to be this really tiny all women’s school,” Taylor said. “And they joined [Miami] and what people say, you know, is that… the agreement was that there would be no sorority houses. And at the time in Ohio, if there were like a certain amount of women living in a house, in ratio to men, if it was over a certain amount, it was considered a brothel. So we didn’t have sorority houses and they’ve just never come back.”

Traditions and standards are created in similar ways as the sorority living situations at Miami: by establishing an influential precedent that is honored throughout time. Many common etiquette rules have stayed so persistent through history because of the generational values that conform to them.

Yet, as technology advances, the understanding and history of etiquette is becoming irrelevant as new ideas of mannerism are created: “don’t be on your phone when having a conversation”, “be careful what you share on social media”, etc.

“I would say [etiquette is] transferred into technology just because I would say back in the day, I mean, obviously you didn’t have to worry about that kind of thing,” Taylor said. “But now with social media, everything that you say and do can be so easily recorded or put out there, that it’s really important to, like keep that in mind, and keep the ideals of your sorority or whatever organization, you’re a part of close to yourself so that you represent them in a right light.”

CULTURAL ETIQUETTE

Etiquette often refers to cultural guidelines for propriety and respect within different establishments. Different cultures have different etiquette guidelines; cultural etiquette pertains to the fluctuations in etiquette across different cultures.

Cultural differences affect areas of etiquette such as hierarchy, deference, punctuality, business, and more.

Sophomore Hana Moussad reflects on forms of etiquette in her Arabic household that varies from those around her.

“If we’re visiting houses, take off your shoes, absolutely. Like if you walk in and your shoes are muddy, that’s disrespectful,” she said. “We always have to take care of our shoes. Like, if you have white shoes and they look dirty it shows a sign of your hygiene and your household.”

Junior Ala Stanek, whose parents immigrated from Poland to the U.S. in the 1990s, noticed that this is a practice that she shares with Moussad, although it is not one that is common in America.

“American people, like they always keep their shoes on inside their house,” she said. “I don’t get that—I always take my shoes off whenever I go to someone’s house.”

Many cultures share the expectation of removing shoes before entering a house, whether it be for spiritual, health or hygiene reasons. For example, in Thailand, the head is considered the most sacred part of the body, so the feet, being furthest from the head, are dirty and most removed from the spirit.

The concept of etiquette in general, however, does not differentiate too vastly between the countries, Stanek observed.

“I don’t know if etiquette is that different from Poland in America,” she said. “It’s just the basics, like being nice to everyone or being respectful to the people that you’re around.”

Due to the fact that many cultures have different forms of etiquette, some cultures’ proper etiquette can appear odd or even disrespectful in other cultures. Moussad noted that her Arabic culture is perceived differently by those around her at times.

“Some people might take it as too strict or too closed off just because I’ve learned to just be present in the moment,” she said.

Despite similarities in social rules themselves, the weight that those rules hold varies across cultures.

“Manners are a lot more enforced in Poland than they are, I’d say, in America,” Stanek said.

While what qualifies as good or bad etiquette varies cross culturally, the goal is the same: to allow people to present the best and most respectful version of themselves possible.

“Everybody has their own culture. Everybody has their different roles and stuff that they do with their family,” Mossad said. “And we’re all just people who, you know, talk with each other from different cultures from around the world.”